Two headings can look identical on paper. Same jumbo. Same crew size. Same shift length. Yet one advances smoothly while the other keeps falling behind. In many cases, the difference is not drilling speed or equipment power. It comes down to drilling patterns and how well they fit the heading, the rock, and the cycle.

Drilling patterns are often treated as fixed templates. Once chosen, they rarely change. In underground development, that mindset causes trouble. Patterns shape how the face opens, how clean the blast pulls, and how much rework follows. Over time, they shape advance rates far more than most crews expect.

Why Drilling Patterns Matter More Than Most Crews Expect

In underground development, a drilling pattern is not just a layout on the face. It is the interface between drilling and blasting, and a major driver of cycle time. A pattern that drills easily but pulls poorly can slow the next round more than a slightly longer drilling time ever would.

Patterns influence how much correction is needed, how the face looks after blasting, and how smoothly the next cycle begins. When problems appear, they often show up later and get blamed on operations downstream, or on equipment that is not at fault.

Seen in context, drilling patterns sit within a broader system of underground mining equipment used in development work. When the pattern is mismatched, the whole system feels the strain.

The Link Between Pattern Design and Cycle Time

Cycle time is not only about minutes spent drilling. It also includes time lost fixing shallow holes, cleaning bootlegs, scaling loose rock, and repositioning for the next round. A pattern that reduces those losses often delivers higher advance, even if drilling itself takes a bit longer.

The Role of the Cut Pattern in Opening the Face

The cut pattern sets the tone for the entire round. If the cut opens cleanly, the rest of the blast has room to work. If it struggles, every surrounding hole works harder, and the blast result suffers.

Cut patterns are not interchangeable. Each has limits, and those limits matter underground.

Wedge Cut and Its Practical Limits

Wedge cuts remain common in development headings because they are simple and familiar. They can work well in competent rock with reliable drilling accuracy. Problems start when relief is limited or when cut holes drift.

In narrow headings, even small deviations reduce free face quickly. The result is poor pull in the cut area, followed by bootlegs that slow cleanup and delay the next cycle.

Burn Cut and Parallel Hole Patterns

Burn cuts rely on parallel holes and precise drilling. When accuracy is high, they can open the face efficiently, especially in hard rock. When accuracy slips, performance drops fast.

This is where crews often get caught. The pattern looks efficient on paper. Underground, small alignment errors close the burn hole, and the cut fails to open as expected. Extra drilling or corrective blasting then eats into advance.

Perimeter and Stoping Holes—Where Advance Is Often Lost

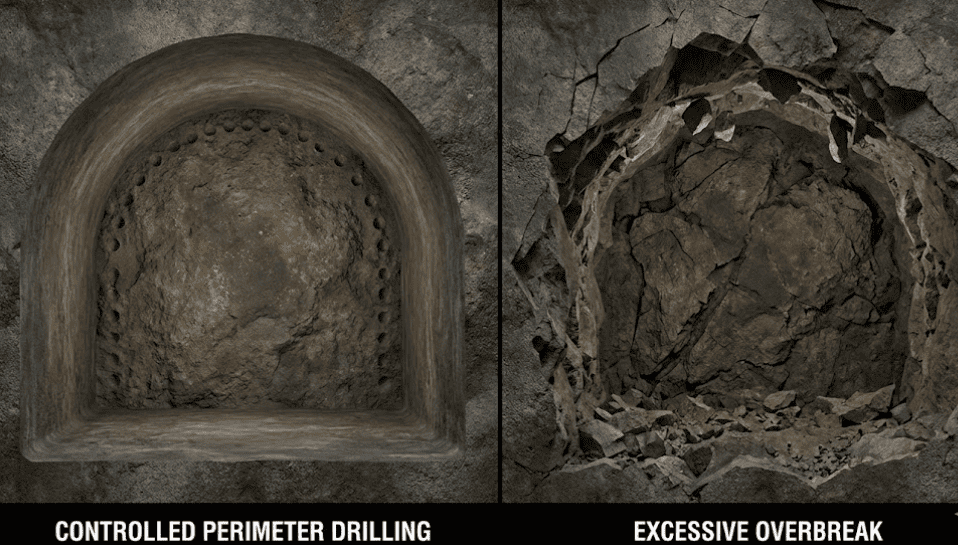

Attention usually goes to the cut, but many delays originate at the perimeter. Poor perimeter control creates overbreak, uneven faces, and extra scaling. These issues rarely show up in drilling logs, yet they cost real time.

A perimeter that breaks cleanly supports faster cleanup and safer access. A perimeter that collapses or leaves loose rock slows everything that follows.

Perimeter Hole Spacing and Overbreak Risk

Wide spacing may look efficient during drilling, but it often increases overbreak in jointed ground. Tight spacing improves control but adds drilling time. The right balance depends on rock condition and heading geometry, not on habit.

How Poor Perimeter Control Slows the Next Cycle

Overbreak increases scaling time and leaves irregular faces. That irregularity complicates positioning for the next round and raises the risk of alignment errors. Advance rate drops, even though drilling itself seemed fine.

Drilling Accuracy and Pattern Sensitivity

No drilling pattern survives poor accuracy. Some patterns tolerate small errors. Others fall apart quickly. Knowing which is which matters.

Accuracy issues usually show up as shallow holes, angle drift, or collar movement. Each one weakens the pattern’s intended interaction.

Hole Deviation and Pattern Breakdown

Deviation reduces effective spacing and relief. In cut patterns, it can close the opening. Along the perimeter, it weakens contour control. Once that happens, the pattern no longer behaves as designed.

When “Standard Patterns” Fail Underground

Standard patterns often come from ideal conditions. Underground headings are rarely ideal. Irregular profiles, mixed rock, and human factors all push patterns beyond their comfort zone. When crews keep pushing instead of adjusting, advance suffers.

Matching Drilling Patterns to Heading Size and Geometry

Heading size changes everything. Patterns that work well in one profile may struggle in another.

Small headings leave little room for error. Large headings can hide inefficiency until it becomes systemic.

Small Headings That Punish Pattern Errors

In 4×4 m or similar profiles, tolerance is tight. Cut failure or overbreak has immediate consequences. Patterns must be conservative, accurate, and easy to execute under pressure.

Large Headings That Hide Inefficiency

In wider headings, poor patterns may still pull. The blast looks acceptable, but cycle time creeps up through extra cleanup and repositioning. Advance rate drops quietly.

How Pattern Choices Affect Downstream Operations

Drilling patterns influence more than blast results. They shape muck pile geometry, access conditions, and how quickly the face can be cleared.

When breakage is uneven, downstream work slows. Irregular muck piles take longer to handle, and clearance becomes unpredictable. At that point, underground mining locomotives supporting development headings feel the impact directly.

From Drilled Face to Blast-Ready Conditions

Patterns that deliver consistent breakage simplify charging and stemming. Patterns that fail force last-minute adjustments and delays. Those delays often cascade into the next shift.

Pattern Errors That Appear as “Logistics Problems”

Poor breakage is sometimes blamed on haulage or scheduling. In reality, the root cause sits at the face. Uneven fragmentation slows clearance, disrupts the rhythm of mine locomotives used in underground development, and delays the start of the next drilling round.

Conclusion

Drilling patterns shape advance rates because they shape the entire cycle. They influence how the face opens, how clean the blast pulls, and how smoothly the next round begins. Patterns are not static choices. They are tools that must match heading size, rock condition, drilling accuracy, and downstream capacity.

When patterns fit the job, advance improves without chasing drilling speed. When they do not, every part of the system pays the price.

A Practical Note on ZONGDA and Development Equipment

ZONGDA (QINGDAO ZONGDA MACHINERY CO., LTD) works with underground mining operations focused on metal-ore development rather than coal-only applications. The company supplies a range of equipment used across development cycles, including drilling, haulage, and auxiliary systems. Its product scope reflects an understanding that advance rate depends on coordination, not isolated machines. For operations looking to reduce cycle disruption, this system-level perspective matters as much as individual equipment performance.

FAQ

Q1: Why does a drilling pattern that worked before stop working in a new heading?

A: Because heading size, rock condition, and accuracy change. A pattern that fit one face may be outside its limits in another.

Q2: Is there a single best drilling pattern for underground development?

A: No. Each pattern has conditions where it works well and conditions where it struggles. Matching matters more than tradition.

Q3: Can changing the drilling pattern really improve advance without new equipment?

A: Yes. Reducing rework, overbreak, and cleanup often delivers more gain than faster drilling alone.

Q4: How much does drilling accuracy affect pattern performance?

A: A lot. Some patterns tolerate small errors. Others fail quickly when accuracy slips.

Q5: When should crews adjust a pattern instead of pushing through?

A: When repeated corrections appear, or when blast results create downstream delays. Those are signs the pattern no longer fits the job.